Home (theory of the ego death and rebirth experience)

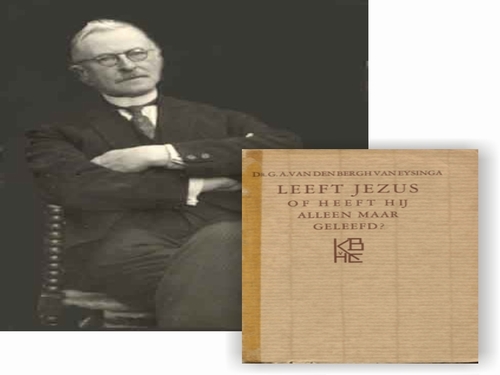

Does Jesus Live, or Has He Only Lived? A Study of the Doctrine of Historicity

van den Bergh van Eysinga, 1930

This is Klaus Schilling's summary in English of G. A. van den Bergh van Eysinga's 1930 article "Leeft Jezus - of Heeft Hij Alleen Maar Geleefd? Een Studie over Het Dogma der Historiciteit". This short book is dedicated to Arthur Drews. van Eysinga comments on many topics that had been covered by Drews, such as in "The Denial of the Historicity of Jesus in Past and Present", and draws additional conclusions. Edited, formatted, and uploaded Oct. 5, 2003 with Schilling's permission by Michael Hoffman; additional copyediting by James O'Meara.

A survey: Van den Bergh van Eysinga.

Search Web: van Eysinga. English only.

The Denial of the Historicity of Jesus in Past and Present - by Arthur Drews

See also: Mystery Religions

Many people today are tired of religious dogmatics. The twelve articles of confession, or the Nicean and Apostolic creeds, are fundamental for Christian belief as expressed in the churches.

Whatever is said in these creeds about Jesus, it is usually considered to be the view held in common among all Christian churches: God's monogenetic son, our Lord, was conceived through the Holy Spirit (Hagion Pneuma), was born from Mary the Virgin, suffered under Pontius Pilate, was crucified, died, was buried, descended to Hell, was raised from the dead after three days, ascended to Heaven, sits at God's right-hand side, and is going to come in order to judge both living and dead.

Nobody should fail to see that these are words about a superhuman, divine being. And all of the elements of the creed are already contained in the New Testament. Not until the modern Enlightenment period of the 18th century did we start to consider and pursue the quest for a merely human Jesus.

An outstanding human preacher replaced the former "son of God". This lead to the modern-era phenomenon of the liberal Jesus cult: the veneration of the optimal human being, the perfect Rabbi, whose example is to be followed.

Many scholars, such as Harnack, make the error of projecting this post-Enlightenment point of view into the ancient times. Modern liberal theology thus propagates the image of the Galilean genius teacher, adapted for the pious minds of our times, whereas Volkmar tried to explain most of the New Testament material from mythic influence from the Old Testament.

Bousset emphasized at a congress on liberal Christianity that the coherent facts on the life of Jesus barely fill a sheet of paper. The preaching of the gospel is a chaotic mixture of church traditions and possibly real words of the Lord. What the gospels unveil about Jesus' emotional life is painted over by the traditions of his communities. The carelessness of the Jesus biographers should thus be ended.

Albert Schweitzer denounced the miserable state of modern theology which tries vehemently to mix history into theology. The Historical Jesus is seen by liberal theologians as the noblest implementation of personality. Dunkmann showed that such a being would be an utter alien in history, especially religious history.

But each conscious reader of the New Testament must notice a difference between the image of Jesus painted in the gospels and the one painted in Paul's letters. Paul doesn't support what most modern theologians try to make people see in Jesus.

Paul seems to turn Jesus into an imposer of community rules, a protector patron of the early church through revelations. Paul knows nothing about John the Baptist, Gethsemane, or the Mount of Olives. Jesus lived, died on the cross, was revived, and all that for humankind's sake -- that's all Paul seems to refer to. The real life of Jesus is not one of Paul's concerns.

The most human Jesus is unanimously that of the Synoptics, especially Matthew and Luke. It's only in a doctrinal sense that Paul appears interested in the humanity of Jesus. But one doesn't get any biographical hints out of the epistles of Paul. Paul presents a myth and divine drama.

Similarly, Jesus being portrayed as world creator can't possibly be a historical fact in the modern sense. The Epistle of Barnabas demonstrates that only through incarnation was it possible that man could bear the parousia (arrival and appearance with power and authority) of the Christ. The flesh behaves just like a curtain, as can already be inferred from Hebrews 10:20: "… since we have confidence to enter the Most Holy Place by the blood of Jesus, by a new and living way opened for us through the curtain … let us draw near to God…" Clement of Alexandria sees the flesh as a window to the Lord.

_________________

The question as it is asked today, whether Jesus is a historical person or not, is not in the spirit of antiquity. Ancient Christians did not know the modern notion of historicity. Neither ancient Catholic nor Gnostic theologians talked about a Historical Jesus.

Marcion denied the fleshliness of Jesus, but Tertullian did not charge him with denial of the reality of the Christ. Catholics and Gnostics diverged in the role of redemption. For Marcion it's a spiritual resurrection, for Tertullian one in the flesh. The concrete carnal reality of Christ is a doctrinal postulate of the church, as much as his metaphysical efficiency is a soteriological postulate of the Gnostics. This is reflected in the divergent understanding of the resurrection: Gnostic 'resurrection' means knowledge of a higher form of existence, while Catholic 'resurrection' means revival in the flesh.

The Gnostic-Marcionite understanding of a 'resurrected' one is that of someone who achieved divine knowledge (gnosis), and the term 'death', in the Gnostic sense, means the lack of this gnosis. In contrast, Tertullian ties the apocalyptic resurrection in the flesh, as derived from the Tanakh, directly to the unique fleshly existence of the pre-and post-resurrection Jesus. John's gospel contains many remnants of the Gnostic perspective.

Apart from the sarcasm and polemics that Tertullian throws against Marcion, it's easily sensed that the relation between the Catholic and Gnostic view is that between a realist and an idealist.

Gnostic docetism is consequently based on the idea that matter is the evil principle: Christ, as the extremely Good One, cannot participate in matter. His birth and death can be but phantasmic events. Marcion lets Jesus descend straight from the heavens, without being born.

Cerinthus made the angel-like Christ enter a particularly sage human at the moment of his baptism down by the riverside of the Jordan, and leave him at the crucifixion. The epistle of John, a Catholic forgery, in 1 John 4 violently denigrates the docetic view as the tool of the devil, and in the Apocalypse of John, as the Antichrist.

The metaphysical Christ of the Gnostics predates the biological Christ of the churches. As Huikstra showed around 1870, Gnostic topics prevail in Mark's gospel, where the human character of Jesus is minimal. And even if, as Hilgenfeld showed first, Matthew's gospel preceeded Mark's, Mark's gospel demonstrates the most original core. Van Manen showed the Gnostic character of the supposable common ancestor of all canonical gospels.

The whole struggle between Catholic and Gnostic Christians was thus about a realistic Jesus of the Catholics versus a metaphysical-idealistic Christ of the Gnostics, not a dispute about "historicity" in the modern sense.

The Gnostic says that the Christ's essence is a perennial, spiritual one, whereas this world is woven of phantasm and error. The Catholic says that this world is divinely created; consequently, the Gnostic Christ is wholly separated from the world, the Catholic Christ is interwoven with it and participates with it in the flesh, and Catholic doctrine identifies the creator with the father of the Christ.

There were Ebionites that considered Jesus as a psilos [?] anthropos, but this can not be seen as an indication of historicity, because it happened, like in the case of Catholics and Gnostics, due to merely doctrinal reasons, not historical ones. There were two sorts of Ebionites: those rejecting and those accepting the virgin birth, as Origen already pointed out. For the former, the Jewish doctrine of monotheism, stricter than the Catholic version, does not allow for a God as man, and thus imagined a particularly righteous man in the natural sense, through whom an angel of the Lord spoke to and instructed mankind. This has been observed by H. Bauke.

The synoptics still say that John the Baptist is the supreme one among the woman-born, and lower than all those who will enter the reign of God. The Manicheans and Cathars continued to use the concerned passages for their docetism, especially Matthew 11:11: "I tell you the truth: Among those born of women there has not risen anyone greater than John the Baptist; yet he who is least in the kingdom of heaven is greater than he." The docetic view didn't replace an existing realistic view, but, quite to the contrary, the docetic view eventually was transformed into the realistic view.

Roman Christianity achieved its decisive advantage over Mithras and other cults by being able to provide a solid historical background for their mystery hero, precisely by using the Tanakh. Without the Old Testament, Christianity would have found itself on a level with Mithras, a hero legend suspended in mid-air. The Messiah legend of the Tanakh rooted Catholic Christianity firmly in the world, as opposed to the cosmophobic Gnostic Christians.

_________________

Pre-Enlightenment Christianity was happy with a supernatural description of Jesus, as distilled from the New Testament and expressed undeniably in the 12 articles of confession, and the Nicean and Apostolic creeds.

With the Enlightenment, the supernatural Jesus was gradually replaced with a natural Jesus, leading to the liberal Jesus cult. The picture of an outstanding Jewish rabbi, adapted for modern society, replaced the concept of the supernatural "son of God". Thus modern liberal theologians like Harnack erroneously project post-Enlightenment consciousness back into ancient times.

The works of scholars such as Bolland, von Hartmann, Drews, and Kalthoff thoroughly refute the implicit assumptions on which Harnack bases his statements. Only the prejudices of modern man support the liberal Jesus cult.

G. Volkmar stresses the mythical influence of the Tanakh for the gospels. W. Brandt sees death and resurrection as the unique facts known about Jesus, a mix of triviality and supernaturalism. Van Mourik Broekman, though a staunch historicist, at least admits that a modern liberal Christian must always be aware of the possibility that historical facts may be disproved in the future, including Jesus' life.

W. Bousset sees the knowable facts about the Historical Jesus as minimal, and painted over by the fantasies and emotions of the early Christian communities and subsequent church traditions. A. Schweitzer sees the ingenuity with which history and faith are mixed as merely reflecting the miserable state of modern theology.

The liberal Jesus is essentially an inflated figure constructed by post-Enlightenment theology. Dunkmann demonstrated that a Jesus constructed by liberal theology would be a monstrous chimera, extremely unlikely in history, in particular in the history of religions.

_________________

According to Dunkman, not much of the Jesus the Historical Jesus cult dreamt together is found in Paul's epistles. While Luke's and Matthew's gospels may give the impression of a human Jesus, Paul's writings make Jesus appear as a patron saint of early Christian community. Paul is silent about such basics as John the Baptist, the Mount of Olives, Galilee, and Nazareth. Jesus lived, worshipped, was crucified, died, was resurrected, and ascended, all for the sake of human race. This does not differ much from what is said about the pagan mystery deities as well. Wrede pointed out that the author of the letters tried to doctrinally give a human face to Jesus.

Having been born, lived, and died, these are commonplaces for mankind, not distinguishing features of a biography. According to Juelicher, the resurrection is the central, core point of Christianity for Paul. What Paul knows about Jesus is a sort of divine drama. According to the Epistle of Barnabas, the carnal appearance of Jesus was necessary for man being able to bear seeing the divine Jesus. Hebrews sees the flesh of Jesus as a curtain, to protect man from the divine light that would blind him. Clement of Alexandria sees the flesh of Jesus as a sort of window.

The question about the historicity of Jesus would make no sense in ancient times. Neither Catholics nor Gnostics spoke about a historical Jesus. The difference between Tertullian and Marcion is spiritual versus fleshly resurrection. For the Gnostic-Marcionite view, 'resurrection' means familiarity with knowledge about the divine, while 'death' means ignorance of divine knowledge. The expression 'overcoming death' thus has at least two fundamentally different meanings. Jesus is constructed according to the divergent understandings of 'death' in the respective communities.

It's a similar opposition as that of realism versus idealism. Hieronymus seems forced to state that docetism predates the church, and could be original Christianity. Matter being the evil principle, it would be improper for the redeemer to be material. Marcion's Jesus descends straight from heaven, without birth. According to Cerinthus, Christ did not come in the flesh, but possessed as spirit the earthly man Jesus. The Christ also returned Jesus back to life.

While a few liberals like Brandts should not be uncomfortable with Cerinthus' version, rational theologians now explain the minor resurrection stories of the New Testament as curing of diseases. Catholicism vehemently condemns docetism, especially in 1 John 4:2: "This is how you can recognize the Spirit of God: Every spirit that acknowledges that Jesus Christ has come in the flesh is from God..."

_________________

The pseudo-Justinian and the Ignatian epistles as well polemically oppose docetism, while expanding the doctrinal necessity of the resurrection in the flesh. The dialogue of Adamantius speaks in the same vein, adding lots of irony to it: everything must have happened only seemingly, so how may Jesus still claim to be the truth if everything is feint and fake? This shows the completely different ways of understanding truth, employed by the divergent persuasions of early Christianity. For the orthodoxy, the New Testament fulfills in reality what is promised by the Old Testament. This fulfillment must be by a real flesh-and-blood man.

The metaphysical Christ is older than the Christ of the churches. Most scholars subscribe to Markan priority. Van Hoekstra already showed the Gnostic background of Mark's gospel in 1871. Jesus is completely possessed by the Spirit, but only upon baptism. Human weaknesses of Jesus are hardly found in Mark's gospel. Jesus is presented as standing apart from mankind. Only demons recognize him correctly. Even if we suppose Matthean priority, with Meyboom and Hilgenfeld, this allows Mark's gospel to be closer to the Gnostic, original gospel. Similarly, John's gospel represents in many aspects an earlier Christianity than that of the synoptics, although the synoptic gospels predate it as written compositions.

The most original presumable gospel may be seen as of Gnostic origin. It denied a birth of Jesus, but not his reality, albeit in a metaphysical sense. The dispute of early Christianity is thus over a metaphysical-idealistic versus a physical-realistic Jesus. For a Gnostic, Jesus has to be thoroughly disconnected from the world, which is seen as an evil principle. The Catholics assume the identity of the Creator of the world and the Father of Jesus, and reworked the gospels and epistles to conform to this acceptance of the world creator.

According to Origen, the Ebionites rejected the virgin birth idea and assumed an ordinarily born Jesus instead, through which an angel of Yahveh worked and expressed itself starting with the baptismal event, as was the case with the prophets of the Tanakh. But this is dictated by the strict Jewish monotheism.

Unlike post-Enlightenment scholars, ancient people could well imagine virgin birth as a reality. Modern-day consciousness relates to that of the Classical era as science to magic, according to H. Raschke.

_________________

The Acts of the Apostles compares Paul with Zeus, and Barnabas with Hermes. It's clearly understood that gods may temporarily turn into humans. In the ancient sense, Jesus may have led a real life as God as much as a man. The reality of Jesus in the ancient sense does not require flesh-and-blood reality. The Life-of-Jesus research anachronistically projects modern notions of historicity and reality onto the thinking of ancient times, sending common sense amok. But the gospels assume a different sense of reality.

Marcionites and similar groups refused to think of the divine in earthly, Jewish ways. According to Tertullian, the common believer back then longed for escaping from the menaces of postmortem penalties in hell. This required the flesh-and-blood reality of the savior, born from a human mother. But that would be a ridiculous contradiction in the creed, which supposes a monogenetic son of God.

The ordinary birth also conflicts with a gospel statement that John the Baptist is the most elevated among those born of a woman, implying straightforwardly that Jesus isn't born in the vulgar manner: Matthew 11:11, "I tell you the truth: Among those born of women there has not risen anyone greater than John the Baptist; yet he who is least in the kingdom of heaven is greater than he."

Antidocetic dogmatics thus occupied a great deal of effort in early Christian orthodoxy. This led to the historization of the idea. The fleshy Jesus was required for the orthodox brand of salvation. In I Corintheans 3, Paul addresses the hylics who are considered as infants who need to be fed with baby food, unable to digest the solid food of the pneumatics: "Brothers, I could not address you as spiritual but as worldly -- mere infants in Christ. I gave you milk, not solid food, for you were not yet ready for it. Indeed, you are still not ready."

The church adapted this systematically: the food for the common people had to be a doctrine about a flesh-and-blood Jesus, suffering and dying as a man, in order to overcome death and thus feed the believer with the hope for temporal immortality they were looking for. This historization, based on Roman and Jewish practical realism, allowed mainline Christianity to get ahead of all other cults and the heresies, whose savior was just an abstract divinity. There's no other way Christianity could have become a stable popular movement.

John's gospel looks like a compromise.

Until the 18th Century, Mercury and Mithras were believed to be historical people. Their cultic hymns are inspired, but not necessarily by historical people: neither is Euripides' hymn on Artemis inspired by a historical Artemis, nor David's psalms by a historical Yahveh. The worshippers of those figures, being thoroughly sure about the existence of Heracles, Dionysos, and Horos, were not historiographers. As expressed by Bolland, the gospel Jesus is thus the historization of the idea of Christ, the dying and resurrecting son of God.

_________________

The Catholic church rejected Gnostic phantastery and misocosmism. They aimed for a practical demonstration of God's love. The gospels are thus assumed to invoke the exoteric belief in Jesus, not for extreme mystics, but for common people around the world. This is only possible with a Messiah thought of fully as a man. While Mark's gospel still contains a rudimentary humanized Jesus, this Catholic concept is realized more completely in Matthew and especially Luke, which can easily be mistaken as a historical report. Only something the multitudes can understand and identify with had a chance of becoming a stable popular movement.

John's gospel merges the abstract Philonic Logos with the historicized Jesus of the synoptic gospels. Loman went further and showed that even the synoptics are not attempting to provide the impression of a historical report in the sense post-Enlightenment people would understand it. A reading of Paul's epistles protests against the image of a biographically determinable Jesus in the epistles.

Thus Christ devolved from the purely spiritual being of the Gnostics to the "fully man and fully God" of the Catholics, and finally to the mere man of the liberal Jesus cult. According to Goguel, the enemies of early Christians criticized the lack of coherence and consistency of the gospels. But this doesn't make them call the tales "untrue" and their figures "unreal". Guignebert noted correctly that the so-called witnesses for Jesus outside Christianity are not really worth much. Both Guignebert and Goguel still refuse to draw the full consequences out of those considerations.

Van Loon wisely did not even ask about historicity and trustworthiness of the gospel reports, but went straight to the examination of the character of the gospel tales. Explaining a Historical Jesus from Paul and the gospels is an audacious hypothesis. The real question is: which hypothesis may best explain the facts? The liberal Jesus cult just picked out raisins from the cake of scripture, according to their taste, when constructing their Jesus.

With the flawed methods of the liberal Jesus scholars, one should also explain Little Red Riding Hood and the snake in the Garden of Eden tale as "essentially historical". Cuvier and Buffon actually performed this fancy task for Genesis. Dutch Radicals take a skeptical stance towards Enlightenment rationalism. Thus van Loon required that we first determine the character of the gospel story before even being able to think about looking for any historical sense in it.

Windisch, a Liberal anti-Radical, pretended to understand the Radical attitude that he denounced vigorously. Obviously he doesn't understand anything at all about the Radical position, because he conflates Radical Criticism with theological polemics. Dibelius is a scholar of the history of form. He declared that the old way of determining historicity or not of a certain element of a tale is flawed and must be superceded by a more scientific one, which asks about the way a certain passage is conveyed to us.

But the old flaws Dibelius seemed to have banned with the new methods returned through the back door: many elements of doctrines about Jesus were explained as reflecting problems of organizing community life, and the remainder that couldn't be explained this way was still thoughtlessly retained as historical. So the history of forms brings no real advance over the Historical Jesus cult.

_________________

The book The Christ Myth, when published by Arthur Drews in 1909, provoked a shockwave of reactions. The public impact was evident in the Berlin dialogue and in the discussion forum of the Federation of Monists. In a protest action by the conservatives, Jesus was declared to be alive. But such a Jesus can't possibly be the Jewish rabbi born around 2000 years ago.

Gerritsen claims that the event of resurrection continued to last through the centuries, and still does. Statements like that make sense once one thinks of the metaphysical son of God, rather than the Historical Jesus cult's construct.

According to E. Meyer, scholar of history, there's not much left of the historical Jesus, but it serves as a frame that everyone may fill with his own colors and figures. Philologist E. Norden, relying on Meyer, thus requires from his students, when assigned to make a report on a given classical author, to construct the personality and life of the same, according to the student's own wild fantasy to supplement the sparsely known facts. The pious mind can't be content with what remains after liberal critics have constructed the Jesus figure, thus pious fantasy is in demand.

Windisch was upset when radical scholars first appeared in academic positions. Many theological faculties, especially German, consider Radicalism to be completely outlawed. The historicity of Jesus is essential for the emotional needs of Windisch-like scholars. Windisch called the radical scholars completely obsolete. For the Radicals, whatever happened 2000 years ago should not be able to conflict with the belief of people today. The liberal Jesus cult insists in a Jesus that has lived once, and can't possibly accept a perennially living Jesus.

The liberal Jesus scholars frame the question about the Historical Jesus as a purely and narrowly historical question, thus religious or theological doctrines and consideration of metaphysics ideas are mandated a priori as having to stay outside of the permitted range of investigation and consideration. Schiller's William Tell makes Swiss patriots feel fine, but that doesn't save Tell's historicity. The mentality of the members of the Historical Jesus cult is to abandon thinking for the sake of simplistic belief. The Radical scholars are accused of being monists that are unable to recognize great personalities.

The stated slavish dependence of the Radicals on Hegel is without any truth. Bolland may have represented Hegelianism, but he was already a radical scholar in times when he preferred von Hartmann over Hegel. The other greater Radicals have been all non-Hegelian (Pierson, Naber, Loman, van Loon, and van Manen). And one of the most vehement anti-Radicals, Scholten, was clearly Hegelian.

_________________

In pre-Enlightenment Christianity, the faith in the divinity of Jesus was the litmus test for Christianity. The liberal Jesus cult turned everything on its head and put the belief in the human Jesus 2000 years ago in the place formerly occupied by the divinity of Jesus. Some Liberals replace the pious rabbi with an apocalyptic prophet, but that's merely the same type of thing -- a religiously minded historical individual -- in a different color.

Some Enlightenment thinkers such as Lessing tried to immunize Christian faith from historical research. Accidental historical truths should not be crucial for faith issues. According to Kant, history may well illustrate, but can't possibly verify or falsify religious faith. Historical and religious belief are firmly distinguished. According to Fichte, historic knowledge makes you smarter, but doesn't lift you closer to God.

According to Schelling, Christ is a symbol for the continuing humanization of God. Hegel sees in concrete history just the point of departure for the more important ideal history. D.F. Strauss built on Hegel. The ultimate unity of humanity and divinity is real in a higher sense. He takes Christ as the idea of the god-man.

People looking for history in the gospel used to think that the truth of Christianity could be found in history.

According to Christian orthodoxy, those who write about the life of Jesus, do so by erroneously abandoning the ideal aspects of Jesus, while Jesus Myth'ers erroneously abandon the factual aspects of Jesus. Dunkmann also wrote about this distinction. Thus orthodoxy seems to be the synthesis of the Jesus Myth'ers and the Life-of-Jesus scholars, contributing the ideal and factual aspects, respectively.

According to Mark 4:34, Jesus taught exclusively using parables: "He did not say anything to them without using a parable. But when he was alone with his own disciples, he explained everything." Parabolic sayings are not factual historical messages. Thus Jesus exclusively used tales of fictional origin. Parabolic teachings are analogies. The analogy may be accurate, and the teaching correct, even if the tale is neither simple fiction nor plain fact. The parabolic tale is just clothing for the idea it expresses. Naturalist rationalism only divided the possible assessments into fact and fiction, at the exclusion of a third possible status.

But parable-based teachings show that it's not the case at all: there's the possibility of validity without being based on fact. The parabolic tale just dresses an idea it expresses. Thomas Aquinas taught in his Summa Theologiae that not all of man's fiction is a lie, but senseless fiction is. Sensible fiction is not a lie, but is symbolic truth. Otherwise one would call the Lord a liar because he spoke in parables and pictures.

Parabolic teachings assume the semblance of factual events in order to express metaphysical truth. It's not for the sake of cheating, but metaphysical or spiritual enlightenment. Bolland correctly emphasized thus that everything that is fact may pass away, but truth will remain eternally. And an accumulation of facts does not constitute truth. Knowing facts does not imply understanding the essence.

_________________

The worth of Goethe's Faust does not depend at all on the historicity of that Dr. Faust, let alone that of the events described by Goethe. Romain Rolland said that very religious spirits recognize the living god in the traces he left in the memories of one people, as much as they could have recognized in a factual incarnation. To the truly religious person, for whom all reality is God, those are two equivalent realities.

According to the Vedanta teachers Ramakrishna and Vivekananda, the historical existence of people they adore is absolutely secondary; truth has to stand above reality. To be able to teach those truths, the avatars and prophets of the Vedanta had to be truth. Vivekananda doubts the historical reality of Krishna, while still worshipping him as the highest incarnation of Vishnu.

In whatever sense Jesus lives, so do Mary, Job of the Tanakh, and Goethe's Faust. Even if the hero of a story isn't historical, the author is. Thus the impression that a real man is "behind" a story can never fail and cheat you.

The authoring of a book describing a Godman is, as such, a factual event, subject to historical and sociopsychological studies. Bolland noted that the gospels still represent the sensible concept of the shining example of the divine in mankind.

The liberal Jesus cult banished all metaphysical thinking from Christianity and turned it into a cult of factuality. Clearly the radical scholars upset people with such a basically and staunchly metaphysical mindset.

Christ can't be seen as an ideal person, but as the ideal of personality. This ideal is not from the fantasy of a single person living in a vacuum, but reflects the life of a community in its social environment, whose voice is the author. The gospel story was received by the community as a divine presence personifying and fulfilling the religious feeling of a whole period. Thus its character is mythical. Later it was transformed into dogmatism. The Enlightenment tried to dispense with both mythology and dogmatism. But scholars should not forget that the gospels were largely written and redacted with the goal of countering the tendencies of heresies.

Jesus the man is an abstraction constructed by the Enlightenment, attempting to distill a natural Jesus from supernaturalist tales.

But even a symbolic interpretation of the gospel tales employs historiology: the Gnostic author or authors of the most original gospel must have been some real person or persons living in an actual, particular social environment and circle. When time was full, divinity revealed itself in history as man or as certain men, but not in the sense that the gospel Jesus became a particular, individual, historical personality.

'Reality' is usually translated in two different ways in Dutch, and those ways are not synonymous. The conflation of them continually causes misunderstandings when talking about the reality of Jesus and God. He who seeks a historical Jesus -- be it, like the early liberal Jesus theologians, as a noble Jewish rabbi, or, like the later liberals, as a prophet supported by an institution -- is he pursuing what was a plain historical matter, or is he pursuing what was actually the expression of the wish of humanity for some spiritual type of redemption?

A scholar of history has to research questions of this sort critically and without bias. Again the analogy to William Tell as the expression of Swiss desire for freedom is used in this context. Those scholars who are also Christians have to understand that the worth of Christian faith does not actually depend on a specific historical Jesus having lived around the turn of the era.

O. Pfleiderer said that it's necessary to admit that both modern and ancient images of Jesus are nothing but creations of humans living in their respective social environments. G. Bertram wrote that such cool objectivity of the present author's work merely indicates a lack of historical-methodological clarity. Does Bertram prefer 'warm' objectivity? Rather, Bertram obviously thinks that objectivity is impossible. The historicity of Jesus is obviously removed from science (ordinary reason and evidence) and is made an exclusive affair of dogmatic belief.

_________________

Many other figures of legend and literature are seen in a similar light, such as Pallas Athena, Don Quixote, Romulus, Yahveh, and Osiris. They "lived" in those real people who contributed to the tales, and are to be understood within their historical context. So these mythic figures have a life, but not in the direct sense held by modern historians.

Goguel noted that many details in the gospels appear in order to specifically imply the fleshliness of Jesus. This shows that at the time when the gospels were written, doubts abounded about Jesus' carnality. Goguel wants to put this forward as a proof of Jesus' historicity. But, just as the post-resurrection hints of carnality are added polemically against the docetic school, also the pre-crucifixion part is painted anti-docetically. And this does not make Jesus a historical person.

Unlike the Gnostic tale of the redeemer descending straight from heaven (for example, in the Naasseni hymn), the Roman Catholic reformer needed a "realistic" tale of a son of God in the shape of an itinerant healer and preacher. Originally, the "realistic" life of Jesus just consisted of birth, passion, and resurrection, but the Jesus lifestory was gradually extended.

The celestial Christ of Paul was morphed into a quasi-historical individual, as Couchoud put it. This gradually increasing reification went hand in hand with the polemic refutation of the Gnostic heresies. The faith in a "living Jesus" was a necessary forerunner for the belief in a "Jesus that had lived". The gospel is a parable about the Christ mystery. Raschke's famous formula concerning the evolution of Jesus from the Pauline metaphysical force of the Gnosis to the quasi-historical Jesus of the gospels is mentioned again.

According to Goguel, docetism was not an assertion about Jesus' historicity, but was merely a theological position, so docetism does not entail a denial of the Historical Jesus. But one would have to admit the same for early anti-docetism as well. Doctrine just stands against doctrine, and neither of them centers on asserting historical facts. The ancient type of historification of the Christ mystery does not turn Jesus into a historical fact.

_________________

Right-winger A. Seeberg considers the gospels to be an elaboration of the fundamental Christian doctrine of the son of God, sent to earth for preaching, miracle-working, passion, death, resurrection, instigation of the apostles, ascension and return to sit at the right hand side of the Father -- the fundamental facts of Christianity. The gospels thus give a historically styled illustration of the basic doctrines of Christianity. Bultman played a similar trumpet.

P.W. Schmiedel seems to reveal a strange sense of humor in his justification for the liberal Jesus picture. He established nine supporting columns or pillars for this picture. These purported supporting columns have been thoroughly refuted by the Radical school, but the Liberals ignore that.

One pillar refers to a saying of Jesus in which he refuses to be called "good". The liberals can't see how the followers of Jesus would invent such a self-denigration of Jesus. But this argumentation is flawed. The Corpus Hermeticum already denies the epithet 'good' to the Logos, and reserves it for the Father. No one could be stupid enough to declare the Hermes-Logos as a historical figure just because its advocates denied its being warranted 'good'. Ptolemaeus Gnosticus says something similar about the Demiurge.

Another pillar is based on Mark 13:32 and Matthew 24:36, where the Father alone, no one else, including the son, know about when the end will come exactly: "No one knows about that day or hour, not even the angels in heaven, nor the Son, but only the Father." From this, Schmiedel dares to conclude the humanity of Jesus.

Another of Schmiedel's arguments concerns Jesus being deemed foolish by his relatives. This embarrassment, so the liberals think, couldn't be the work of later Jesus worshippers. But that's pure nonsense, as the opinion of those relatives, in the eyes of the Christians, just presents the opinion of the conservative Jewish people, who can't recognize his "son of God" status.

Schmiedel also uses Jesus' famous words on the cross, about having been forsaken. But those are copied almost verbatim from the Psalms and Isaiah.

In Mark 6:5, Jesus admits being unable to work wonders:

Jesus said to them, "Only in his hometown, among his relatives and in his own house is a prophet without honor." He could not do any miracles there, except lay his hands on a few sick people and heal them. And he was amazed at their lack of faith. -- Mark 6:4-6

But his inability to work wonders is due to current circumstances; otherwise, it would boldly conflict with Jesus' usual aptitude for working wonders. Faith in Jesus is required, to allow him to work wonders. In no way does this make Jesus humbly confess his mere humanity and thereby also implicitly assert his historicity.

_________________

Some other of Schmiedel's "pillars" are dismissed. Windisch did not follow all of Schmiedel's arguments, but only some of them, adding his own arguments. The Radicals were tired of the poor excuses for arguments that were produced by the Liberals.

According to Matthew 11:19, Jesus is a drunkard and a glutton: "The Son of Man came eating and drinking, and they say, 'Here is a glutton and a drunkard, a friend of tax collectors and "sinners"..." No one would invent this for a worshipped god-like figure, so Jesus must have been a human -- so the liberals want to make us believe. But that's absurd, because Hercules was shown in an even worse manner by his believers. One would not prove the historicity of Hercules this way. Windisch understood this as a cheap parallelism.

Something even more baseless than all of Schmiedel's wobbly pillars is the common methodological mistake of assuming as most factual those verses of a report that don't fit the general tendency of the report, such as the denigration of Jesus in the pro-Jesus gospels. That method may be workable for historical reports, but that method is plain and utter nonsense, elsewhere; for example, the negative aspects of Homer's description of Zeus can't be taken as factual just because they are negative.

Von Soden nonsensically used the congruence of sayings in the various synoptics as a proof of their authenticity. Juelicher abuses the references to Jesus' social environment, and the fact that Jesus matches with this environment, as arguments for historicity.

Guignebert's apologetics don't make those most ridiculous of mistakes, but he still thinks that for unprejudiced readers, the gospels contain a sharp outline of Jesus' human existence, because, for example, no divine being would eat, drink, and get tired.

As opposed to the pre-Roman Hellenic mystery deities, the Romans developed the concept of the Stoic wise man who represents the ideal of the divinization of man. This emphasizes the role of man more than the Greek forerunners did. Finally this picture gets extended to a divine mystery being that turned into a suffering human for the sake of the human race. The Catholic realism fits well with the Roman spirit. The Stoa is the forerunner of Catholicism in this sense. The legendary Heracles and the historical Cyrus were similarly used in the role of the perfectly wise man.

_________________

For the Socratics, Socrates was the perfectly wise man. Cynics like Antisthenes and Diogenes of Sinope considered themselves as such. Also two of the early Stoics, Cleanthes and Zeno of Kition, did in a similar way. The Stoic ideal was gradually aimed higher and higher. Cicero thus considered the wise man as not yet having existed. Plutarchos plays the same trumpet, also Sextus Empiricus. Seneca, in a similar vein, wonders rhetorically where to find him, as even the best philosophers he knew about were pretty far from the ideal.

But in imperial Rome, Stoicism returned to considering the ideal of the wise man to be attainable. Thus Epictetus deemed Diogenes and Heracles to be divine, while Cleanthes, Zeno, and Socrates qualified as wise men. Cato was also seen as an ideal.

One should not be surprised that scholars were tempted to think that the Christ was alluded to in the writings of the Stoics, especially Seneca's 120th letter. There Seneca states that the understanding of the Good one follows an instructive historical example. By the example of noble men we conceive a picture that is impossible to obtain by mere speculative thinking. Traits of the ideal image have been realized in great men, and were projected and magnified into the ideal wise man.

According to Philo Alexandrinus, Moses is the incarnate Stoic ideal of the wise man. Philo represents the Logos, divine reason, as the High Priest and Messiah. The Logos may be realized only in a man free of sin, which is deemed to be close to impossible. Mainline scholars use to say that Philo's Logos is partway between an impersonal spiritual being and an allegorical personality, and that this is quite different from the Christ of Christian theology.

But Philo frequently describes something that can easily be seen as tantamount to an incarnation of God: God may appear as a human in order to help those who beg for his help.

The Roman church correctly recognized that the idea of godmanhood, in order to appeal to the multitudes, must be presented in the form of a human life. Thus as an idea, the historicized Jesus figure led the Roman church to its success. In John's gospel, the Logos is incarnated in a similar way as in Philo's writings. John's Christ-Logos is a divine being which is to be imagined in a human shape. The synoptics are more thorough in the anthropomorphization of the Logos, but are not different in essence. Purely mythological conceptions have no broad propagandistic value.

_________________

For the Cynics, Hercules represents the embodiment of virtue. The acts of Hercules read as a victorious struggle against the vices of the world. He penetrated into the underworld, and returned victoriously to heaven. Thus he opened the way for the followers seeking release from the bondage of the passions and temptations. The path from earth to the stars is not easy and lightly taken.

The Stoics, successors of the Cynics, forged the Hercules myth into an allegory about virtue and its representations. Christ unites in himself the Platonic idea and the ideal of the Stoic wise man.

Seneca's Hercules Oetaeus presents Hercules as the son of God, appearing on earth in order to suffer for the sake of the human race, overcome death, and be raised to his father. There are many parallels in a wider sense with the passion of Jesus, but one does not need to assume a direct impact. It shows instead that the concept of the passion and sacrifice of the son of God may be germinally traced to Roman Stoicism.

Guignebert sees the gospels as emphasizing the passion and resurrection, whereas Jesus emphasizes his own life and works. But those works are essentially thaumaturgy and are otherwise supernatural. Godmanhood is linked inseparably to the life and works of Jesus, as an illustration of his role that culminates in passion and resurrection.

The synoptic gospels should be seen as an attempt to make the godman appear in a thoroughly human light, for the purpose of making it appeal to the unsophisticated multitudes, as the exact opposite of the esoteric elitism of the Gnostic heresies.

Primitive human traits were common in the description of deities. Kronos is hungry enough to devour Poseidon and Hades. Zeus falls asleep through the agency of Hypnos. Wotan cries at the death of Baldur. There's absolutely not the slightest reason to see such assigning of human traits as anywhere near proving the humanity of Jesus.

And Jesus does not actually emphasize just his life and pre-crucifixion works. But the consoling role of his death is anticipated in various spots in the gospels. If one dismisses those passages as community interpolations, one will arrive at a different picture, but that's blatantly arbitrary.

Many stupid arguments have been invented by those scholars -- for example, the bread for the children in Mark 7:27 being the gospel for the Jews, while only the crumbs remain for the 'dogs'; that is, for the Samaritans and Gentiles:

"... a woman whose little daughter was possessed by an evil spirit came and fell at his feet. The woman was a Greek, born in Syrian Phoenicia. She begged Jesus to drive the demon out of her daughter. "First let the children eat all they want," he told her, "for it is not right to take the children's bread and toss it to their dogs." "Yes, Lord," she replied, "but even the dogs under the table eat the children's crumbs." Then he told her, "For such a reply, you may go; the demon has left your daughter."

They want to see this conflict between groups as a proof for Jesus' historicity. But those just demonstrate the schismatic tendencies in early Christianity, but they can't possibly be used to prove a historical, fleshly messiah.

_________________

Everything in the Paulinics circles around the crucifixion, so the crucifixion must therefore be a key article of faith. But Paul never talks about a heroic, human, altruistic passion -- only the martyrdom for a firm conviction. Paul is as convinced of the resurrection as the crucifixion. They relate to a cosmic drama, as opposed to an event under Pontius Pilate.

Guignebert says that Paul is not talking historically about Jesus, because Paul is a Gnostic and thus glorifies Jesus in a phantastical manner. Guignebert ironically makes this into an argument for Jesus' historicity, as Paul could not mythify Jesus if there were no historical one. This is a cheap rhetorical trick. A typical procedure of liberal critics is to silently assume that which is to be shown.

Many scholars, such as Goguel, ridiculously conflate the doctrine of carnality with historical reality.

H.G. Cannegieter pointed out that the gospels are like a celestial theater play projected down onto earth. The epos suffers from the foreknowledge of the hero. Modern ignorance of the environment misrecognizes the divine being as a mere man, shifting the dramatic moment from the hero to the mundane sociopolitical environment. Cannegieter judged that the previous generation of scholars degraded the New Testament epos to a banality. But the current generation of scholars in the early 20th Century is no different.

G.A. Huivers notes that all that is written about Jesus of Nazareth in the New Testament lived in the heart and mind of whoever wrote about it.

Dr. Vloemans stated that, like all great people in history, and even more so, the clearly greatest man in history, Jesus, has been painted over by legends. That's the infamous recipe of the Liberal Critical School once again: Jesus, who was classically understood to be a superhuman being, is dithyrambically replaced with the greatest human being ever, instead of doing one's historiological homework.

Vloemans thunders that the Radical school is easily refuted by a few lines of Tacitus. But that's pure nonsense. Even if one does not consider the annals as a forgery from Renaissance times -- such as Poggio Bracciolini -- or consider the relevant passage as an interpolation, the futility of using Tacitus apologetically is easily seen. Tacitus mentions Christians, named after a certain Christ who lived and was executed in Pilates' Palestine. Tacitus writes this during the times of Trajan, and may have had access to the legends of the early Christians that already circulated around then. But this doesn't make those legends history.

Windisch abuses Tacitus apologetically, saying that in such a short period as between Tiberius and Traian, such a bombastic legend couldn’t possibly have developed, forming such an extensive enmity to Christianity. But the historical existence of that hostile attitude is nowhere near provable, and we should suspect that a neutral attitude was held toward Christianity.

Dupuis already figured that Tacitus might as well have written: the Brahmani are named after a certain Brahman, who lived long ago in India. This certainly would not entitle scholars to assume the historicity of Brahman. Only in the case of Jesus they act differently. And, if Tacitus had truly used Roman archives, he would as well have mentioned the name Jesus.

_________________

Vloemans not only moves W. B. across the ocean [?], and claims that Smith's main hypothesis is that the passion was astral myth , but also repeats the accusation that Jesus Myth'ers, in this case Smith, Kalthoff, and Drews, are just Hegelians. Vloemans demonstrates his lack of knowledge of Hegel's works, and still dares to call himself a scholar of the history of science.

Hegelians are accused of the general trait of denigrating the greatness of great men, but this accusation is easily disproved by pointing to the Introduction to Hegel's Philosophy of History. Bruno Bauer is similarly accused of denigrating the greatness of great men -- but Bauer never in fact denied that the author of the gospel story must have been some truly great man.

Vloemans abused the writings of Flavius Slavonicus as examined by Eisler, groundlessly presenting that version as more original than the koine version. The passage in Slavonicus is almost a summary of the gospel story. Alas, Jesus is not mentioned by name.

Most scholars have by now abandoned the assumption of integrity of Josephus XVIII 3:3:

Now there was about this time Jesus, a wise man, if it be lawful to call him a man; for he was a doer of wonderful works, a teacher of such men as receive the truth with pleasure. He drew over to him both many of the Jews and many of the Gentiles. He was [the] Christ. And when Pilate, at the suggestion of the principal men amongst us, had condemned him to the cross, those that loved him at the first did not forsake him; for he appeared to them alive again the third day; as the divine prophets had foretold these and ten thousand other wonderful things concerning him. And the tribe of Christians, so named from him, are not extinct at this day.

Josephus XX 9:1, the passage about the execution of James, the brother of one named Jesus, is too suspicious to be used seriously. If this refers to an authentic 'Jesus', it must actually refer to the High Priest named Jesus bar Damneus, who is specifically mentioned a few lines later:

Festus was now dead, and Albinus was but upon the road; so he assembled the sanhedrin of judges, and brought before them the brother of Jesus, who was called Christ, whose name was James, and some others, [or, some of his companions]; and when he had formed an accusation against them as breakers of the law, he delivered them to be stoned: but as for those who seemed the most equitable of the citizens, and such as were the most uneasy at the breach of the laws, they disliked what was done; they also sent to the king [Agrippa], desiring him to send to Ananus that he should act so no more, for that what he had already done was not to be justified; nay, some of them went also to meet Albinus, as he was upon his journey from Alexandria, and informed him that it was not lawful for Ananus to assemble a sanhedrim without his consent. Whereupon Albinus complied with what they said, and wrote in anger to Ananus, and threatened that he would bring him to punishment for what he had done; on which king Agrippa took the high priesthood from him, when he had ruled but three months, and made Jesus, the son of Damneus, high priest.

Thus it's ridiculous that modern scholars still try to use the passage as a proof for the historicity of the gospel Jesus.

Eisler's dogmatic axiom is that Flavius Josephus, as a Pharisee and a friend of the Emperor, must naturally have written against Jesus. Eisler vehemently pushes the thesis that Christianity can't be explained without the existence of a historical Jesus who was a messianic rebel against Roman imperial presence and the temple militia.

Liberal professor van Plooy, who employs Eisler as a comrade in arms against the Radical school, says that for the Jesus Myth'ers, who deny the historical Jesus, documents like Flavius Josephus are disastrous. But Eisler makes Jesus into a militaristic zealot, thus the remedy becomes worse than the disease. Therefore Plooy retreats to saying that the witness value of Josephus isn't really that great. The gospel data are much more plausible. But what data?

After van Plooy's retreat, Windisch thunders Flavius Josephus against the radical school, ignoring that Jesus isn't even named as such.

Both van Plooy and Windisch also ignore Eisler's statement that there's no reliable information about the historical Jesus to be found in Christian sources.

van Plooy thunders that even if there were no extrachristian witnesses for Jesus' historicity, the Radical paradigm would have to be abandoned before long, because the multifarious early Christian communities that existed in the first two centuries can't possibly be explained without a historical Jesus. In history, the individual personality is always of priority, never the social environment.

_________________

But not all of the men that gave raise to large movements are even known by name. And they may not be confused with the legendary heroes the movements adored, in the case of founders or reformers of religions. The prophesies of the Tanakh were works of historical prophets, but one may not conclude that Yahveh, whom they worship, was a historical man.

Since earliest times, the Talmud was misused to support Jesus' historicity. Windisch does so, pretending to build on J. Klausner and Eisler.

The epithet "ben Panthera", found in the Talmud, is of particular interest. Klausner derives 'Panthera' from the Greek term 'parthenos', meaning "virgin birth". Windisch follows silently. But why would the rabbis need to use the Greek term 'Parthenos'? This epithet for Jesus couldn't possibly have originated from orthodox Jewish oral tradition, but rather from the gospels.

The derivation from the above is not likely, anyway. And the similarities between the gospel's Jesus and the Talmud's ben Panthera are vague. The late dating of the Talmud makes its independence from gospels and other Christian sources unlikely.

Many other Talmud figures have been identified with gospel figures. Jacob of Kephar Sekanj, student of Yeshu Hannosri, has been read as James, son of Zebedee.

According to Windisch, the Tanakh doctrine of the Messiah is the backbone of the New Testament savior. From this, Windisch derives the historicity of Jesus. For how could the Christians declare that the Christ has come, if Jesus was not a historical personality? But that argument is ridiculous, because the mainline Jews never believed in the messiah of the gospels.

In addition, from the Book of Enoch we infer that Enoch is called the "son of man". Would one infer from this that Enoch was historical, too? The letter of Judah relates that Enoch was a prophet, just like Windisch's Jesus. So why does Windisch not defend Enoch's historicity?

The messianic element should be seen as part of the later Judaization of the original gospel.

_________________

The church fathers arrived at the dating of the gospels using the Tanakh prophets, especially Daniel. The name 'Jesus' is derived from Yah(veh) and sosei (absolves), in agreement with Matthew 1:21: "She will give birth to a son, and you are to give him the name Jesus, because he will save his people from their sins."

J. de Zwaan thinks it impossible that Alexandrine diaspora Jews could have made up the teachings of Jesus as told in the gospels. According to de Zwaan, diaspora Jews who were educated in Hellenic philosophy couldn't possibly have thought that a Jewish rabbi was crucified under Pontius Pilate, descended to the underworld, preached to the demons there, was resurrected in the flesh, and then ascended, because the idea of resurrection in the flesh was too unphilosophical for them.

But that argument anachronistically ignores that the resurrection of the flesh is merely a secondary development in Christian doctrine. The Gnostic and Marcionite Christians didn't support a fleshly type of 'resurrection'. The resurrection of the flesh is consequence of the Judaization that was necessary in the process of making Christianity a religion for the common people.

De Zwaan also ignores the words of the prophets of the Tanakh who form the basis for the crucified Jew as a mystery god. De Zwaan's rhetorical question "What philosopher could have come up with a story of a worshipped crucified Jew?" is thus ridiculous.

Drews' statement about Christianity depending vitally on Jesus conceived of as a man goes too far, and assigns too much competence to the clerics, as if they had the monopoly to decide who or what is Christian. History knows about a variety of versions of Jesus that have as much claim for authenticity, including the Jesus of the docetists, a metaphysical principle; the Jesus of Hegel, the idea of the unity of man and god; and other versions. The prejudice of thinking that the best conceptions of Christianity and Jesus must be the earliest conceptions has to be overcome.

The attitude of the Dutch radical critics is neither that of a medieval nor Enlightenment believer, but that of a modern researcher, looking for the deeper sense of circulating concepts and forms of belief.

Home (theory of the ego death and rebirth experience)